On Being a Midwife in the 17th Century

On Being a Midwife, a Guest Post from Carole Penfield

On Being a Midwife, a Guest Post from Carole Penfield

(NOTE: This Guest Post was published on Regina Jeffers “Every Woman Dreams” Blog on 1-10-22)

During the Georgian and Regency eras, and even earlier, most women who were “breeding” worried a great deal, as these were the most dangerous years of their life. Two of Jane Austen’s brothers lost their wives in childbirth, so she understood pregnancy could lead to death. There was a general concern for a woman’s welfare during breeding, including avoidance of unnecessary travel. In Sense & Sensibility, Mrs. Jennings tells Elinor that her daughter Charlotte Palmer expects to be “confined” in February and should not have taken the long (undoubtedly bumpy) journey to Barton Park. In January, Charlotte is back in London, busily entertaining guests and taking the Dashwood sisters shopping. She apparently does not allow her delicate condition to interfere with her social life, probably laughing it off.

The following month, the newspapers announced to the world, that the Lady of Thomas Palmer, Esq. was safely delivered of a son and heir… an event highly important to Mrs. Jennings’s happiness. She spends every day with Charlotte and attributes her daughter’s well doing to her own care. (S&S, Chapter XIV)

Jane Austen does not describe the actual details of Charlotte’s lying-in. Most women of the upper classes gave birth at home, assisted to some extent by female relatives and female servants, but all these were subordinate to the midwife who was summoned once labour had begun.

I did extensive on-line research about the history of midwifery before writing The Midwife Chronicles series. Midwives have been around since Biblical times. These women cultivated healing herbs and passed down their formulas from generation to generation. Although denied the advantage of formal education, being barred from books and lectures, early midwives learned birthing skills from each other and passed on knowledge to their daughters and granddaughters. In France, where my first novel takes place, midwives were called sage  femmes (wise women).

femmes (wise women).

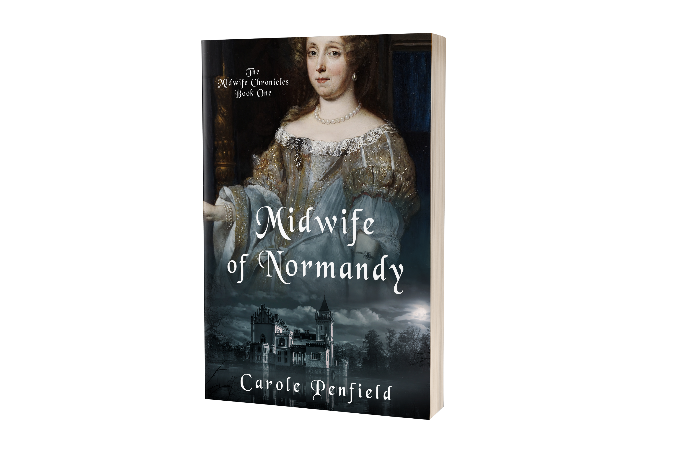

Midwife of Normandy (Book One of The Midwife Chronicles series)

Not every young maiden in 17th century France dreamt of becoming a midwife, but my strong-willed protagonist Clare Dupres was anxious to learn the skills of midwifery passed down from her ancestors, including the secret formula for a “magic” elixir, which provided a pain-free birthing experience. By offering the elixir exclusively to aristocratic women, Clare saw a way to rise from poverty and achieve female independence by engaging in a profession. She was highly successful and rewarded handsomely with gold coins and jewels. One of her wealthy patients was Lady Louise, Marquise of Montjardin who had befriended Clare.

The following excerpt from Midwife of Normandy occurs when Clare is summoned to Chateau Montjardin for the impending birth of Lady Louise’s fourth child. A Catholic priest sits outside the door, praying for the soul “struggling to be born in there.” He tries to convince Clare, a Huguenot, to convert, but she slides by him and enters the room.

(Charlotte Palmer’s birth chamber likely matched the description in this excerpt.)

Chapter 18 (excerpt)

Clare almost choked at the stifling-hot atmosphere. Lady Louise’s room had been transformed by the servants into a traditional confinement chamber. The fire was blazing, the shutters closed, and heavy drapery covered all doors and windows. Even the keyholes were plugged, to keep evil spirits from stealing the breath of the newborn, along with other superstitions that made no sense to Clare.

She folded back the shutters and cracked open the window, letting in fresh air and natural light. Just as Maman had taught her.

Lady Louise was calmly sitting up in bed, dressed in a soft linen shift edged with lace. Around her shoulders was a brightly patterned shawl woven of fine English wool, which Clare recognized as one of Jacques’s imports. Louise was busy buttering a roll.

“Why, look at you!” Clare scolded. “I thought you sent for me at this ungodly hour because you were in travail.”

“The pains stopped and I grew hungry.”

“Put down that roll and let me examine you. Can you still feel the child kicking?”

“Yes, very strongly,” she said. Clare removed her gloves and put her hands on Louise’s swollen abdomen. She was reassured to feel movement. Next, she pulled a horn-shaped implement from her birthing bag, pressing one end on the stretched skin and the other end to her ear. To her relief, there were no evident sounds of distress.

“Does it sound like a male child? I do so long for a boy!”

Clare laughed. “I know of no sounds that indicate the sex of the unborn child. I listen for other reasons.”

“Monsieur le Marquis would be delighted if it were a son, after the disappointment of the three daughters I have given him. You would receive a generous reward for a boy,” she said enticingly. Then a shadow crossed her face. “I’m aware my husband has fathered several male children by his mistresses, but he needs a legitimate son to inherit his title.”

“Dear friend,” Clare responded, “if I had the power to determine the sex of a child, I would only deliver baby boys. Then indeed I should become famous and exceptionally wealthy. But alas, an equal share of baby girls is necessary to ensure future wives for the baby boys.”

Lady Louise looked perplexed for a moment. Then she nodded. “Oh, I see. How clever of you, Clare, to figure that out. Now if only you could find a way to tell the sex of this child kicking my insides.”

“Well, we will have to wait.” Clare spread a clean cloth on the table next to the bed and began to set out her birthing tools. This might be a false alarm, but best to be prepared. Seeing the growing concern on Louise’s face, she pulled over a chair and tried to distract her until the pains resumed.

Leaning toward her friend’s left ear, Clare whispered, “I think Father Benedict is listening at the door. Did you send for him?”

“No. I didn’t realize he was here. He often invites himself for dinner, but rarely bestirs himself for breakfast. I wish he would leave. There is no need for him to be standing outside my bedchamber.”

“Let’s confound him by speaking in English,” Clare suggested quietly, wanting a chance to chat with her friend without being overheard.

“Yes, let’s! He can be meddlesome at times.”

Clare remembered her English from Pierre’s books. As a young girl, Louise had the benefit of an English governess. The two friends began conversing in the foreign tongue. Had they been able to see the priest’s consternation as he held his ear to the door, they would both have been amused.

“Perhaps your cousin thinks I will try to convince you to become a Huguenot,” said Clare.

“How shocking that would be! But highly unlikely, my dear friend. I would be banned from Court. You and I both know how King Louis feels about his heretic subjects.”

Clare frowned, remembering the royal edict that had prevented Pierre from studying law, forcing him to leave the country. But then again if Pierre had stayed, she might never have met Lady Louise. Strange how things sometimes work out.

“You don’t think of me as a heretic, do you?” Clare asked.

Louise hesitated for a second, then said, “Of course not. I know you are a Christian. But wouldn’t life in France be easier for you if you agreed to convert to the Church of Rome?”

“It might, but Jacques would get rid of me and keep me from ever seeing my children again.”

“I understand. To lose one’s children would be a terrible loss for any mother.” It was a troublesome thought, but true. Both women knew that in France, fathers legally owned their offspring—mothers had no right to them.

“Speaking of children,” said Clare, “how are your three daughters doing?”

“Praise the Lord, they are all in good health. My husband is already arranging suitable marriages for them.”

“Already? Surely, the eldest cannot be yet eight years of age?”

She shrugged. “They are ten, five and two. It is not too early for their betrothals. And what of your son and daughter, Clare?”

“They thrive on the country air. Jean-Pierre resembles his father, physically and mentally. Slow, patient, and deliberate. He wants to be a soldier someday—sometimes he sits for hours, playing with his tin soldiers. Lately, though, he has developed a stutter and fear of the dark, claiming there is a ghost who roams the nursery at night.”

“You are fortunate to have a son,” said Louise. “What of your daughter?”

“She has an innate curiosity of the world around her, constantly asking questions. She can outrun her older brother and learned to read before he could master his letters. Lucina is destined to become a midwife one day?already wraps her baby dolls in swaddling cloths, as my mother taught her.” Clare choked back a sob. Maman had died last year, and the memory of the loss was still fresh in her mind.

“Lucina, such an unusual name,” remarked Louise. Her three daughters had common French names: Daphne, Marie-Thérèse, and Hélène. Although Louise was a friend, Clare felt it best not to tell her that little Lucina was named after a pagan goddess, so she simply said her mother had chosen the name.

~ ~ ~

After conversing in English for several hours, Clare began pushing up her sleeves. “Louise, it is possible that you became alarmed by false, early pangs. Since I traveled all this way, I will examine you to see if you are in true travail. But first I must wash my hands.”

“You there,” Clare called to the wet nurse?the wife of a farmer, who had recently given birth to her own child, but had been hired to suckle the Montjardin child. “Ask the servants to fetch Madame Dupres a basin of hot water and a bar of soap.”

When the wet nurse left to do the lady’s bidding, Louise asked Clare why she engaged in such unusual practice. “My other midwives never washed their hands.”

Despite the extreme heat in the room, Clare felt a chill. She bit her lower lip and considered how to respond to this question. Her impulse was to laugh and say, “To keep the demons at bay.” But this was not the time to jest. She thought back to Maman’s admonitions. Never voice superstitious ideas to a woman in travail. What if something were to go wrong in the birthing process? You could be blamed and branded a witch. You could be brought to trial and those carelessly uttered words used against you. Do not forget the memory of your great-great-grandmother—may she rest in peace—who was burned at the stake because the woman she attended was brought to bed of a deformed infant.

Clare knew there were still ignorant, uninformed people who believed midwives were witches due to their skills in an area of life that was a mystery to many people—especially men, since midwifery was a profession dominated exclusively by women. So, Clare was careful with her words.

“Is handwashing really such a strange practice, my friend? Do you not wash your own hands before meals?”

“Yes, I suppose I do.”

“Washing my hands when attending a birthing is simply a habit taught me by Maman. I do not know if cleanliness helps, but I do it anyway. What harm can it do?”

“Oh, I see,” said Louise. Clare thought her patient looked like a fragile porcelain doll, sitting in the sumptuous bed.

The servant carried in a steaming basin, along with a fragranced bar of luxurious milled soap. As Clare scrubbed her palms, fingers, and arms, she heard a loud moan.

“Ohhhhh. The pains have started again and I feel like I’m sitting in a puddle of rainwater.” Clare moved quickly to the bed and checked?clear fluid, no blood—all good signs.

“Louise, your water has broken. Your child is ready to greet the world.”

A shadow passed over Lady Louise’s face. She reached for Clare’s hand. “I am suddenly very, very afraid. Mon Dieu. Will I die?”

“There’s always a slight possibility. It’s in God’s hands. But with His help, I will do my utmost to save you and the child?with as little discomfort as can be managed.” She poured a small, carefully measured dose of elixir, because Louise was petite, and pressed the potion to Louise’s lips, urging her to swallow.

Louise grimaced and turned her head away. “Ugh, it smells rotten.”

“Yes, and it tastes worse than it smells. I know from my own experience at Lucina’s birth. But I promise, it will help you bear the pain.”

~ ~ ~

Four hours later, Clare finished delivering the child. Why, she thought with deep satisfaction, I believe I could do this in my sleep. As she wrapped the leavings and the pink ribbons in her birthing bag, she heard angry voices out in the corridor. She recognized the Marquis’s loud voice demanding to know why Madame Dupres was with his wife. Had he not given explicit instructions to call Madame Larque, the Catholic midwife, if his wife went into travail during his absence?

~ ~ ~